If you’re reading this blog, then you’re probably already a strong advocate for public transit. So am I. But that doesn’t mean that every statistic in support of our position is the unvarnished truth. And when it comes to how earth-friendly our modes of transportation are, there’s reason for skepticism.

Could public transit help make the world a cleaner, greener place? Sure. Does it?

First the good news

APTA, the transportation industry lobby, can give you all the statistics you want about how buses and trains reduce environmental impact. Public transit, according to APTA:

- Saves Americans 11 million gallons of gas a day;

- Saves 340 million gallons of gas per year just from running idle in congested traffic; and

- Prevents more carbon dioxide each year than that required to generate the electricity to every household in New York, Atlanta, Denver, Los Angeles and Washington combined.

Nobody credible disputes that cars, SUVs and pickup trucks crank out over a billion tons of greenhouse gases each year. Taken as a single class, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, they’re America’s second-biggest source of carbon dioxide emissions, right after coal-fired power plants.

Here’s what I can tell you about the prospects for coal. Last year’s Cross-Country Local – the first trip across America on public transit – took me through a big chunk of Texas. Between Abilene and Colorado City, I looked out the window of the CARR paratransit van and saw nothing but wind turbines churning in the prairie skies all the way to the horizon in all directions. When you think of Texas, you think of oil. And yet the Lone Star State has the capacity right now to produce about 18,000 megawatts/year. That’s 9 percent of Texas’s electricity already, and it’s still early days. If Abilene, Texas, is switching to renewable, lower-polluting energy, then coal is doomed. Argue the science if you must, but you can’t argue with the market.

So the logical next step is to see how we can reduce the environmental impact of internal combustion. And wouldn’t the best place to start would be the daily commute?

No, actually not.

Photo credit: Texas Wind Farm, William Freedman

Healthy skepticism

Before we serve our position, we need to serve the truth. One is merely difficult to change; the other is impossible.

First, commuting isn’t the culprit, just the accessory. According to AASHTO, an industry group for state highway department managers, almost two out of every three miles traveled by household vehicle are completely non-work related. Such chores as dropping off kids or picking up groceries on the way to or from work are counted within the commuting figure.

Second, although some indicators suggest that the quantity of commuting trips per person has been a constant in American life since at least the 1960s, evidence suggests these trips have gotten shorter as businesses have moved into the exurbs.

For non-work as well as work purposes, the market and the regulators have both been pounding the drums for cleaner-burning vehicles model year after model year. This goes for buses and passenger vans as well as household vehicles, and maybe there’s some good news here for transit. The average car on the road is 11.4 years old while the average full-sized city bus is only 8. This is at odds with my own anecdotal experience, that there’s a two-tiered structure in transit, with some agencies getting all the shiny new toys, and others running decades-old rust buckets. So I’m eating my own cooking when I say it’s easier to change positions than facts.

But one of the biggest hurdles to getting to the truth when comparing the carbon footprint of private cars to those of public conveyances is focusing on the actual passenger load. According to the Freakonomics blog, that bastion of contrarian thinking, buses aren’t any more filled to capacity than cars.

“At any given time, the average auto has somewhere around 1.6 passengers,” writes Eric A. Morris, “and the average (typically 40-seat) bus has only about 10.”

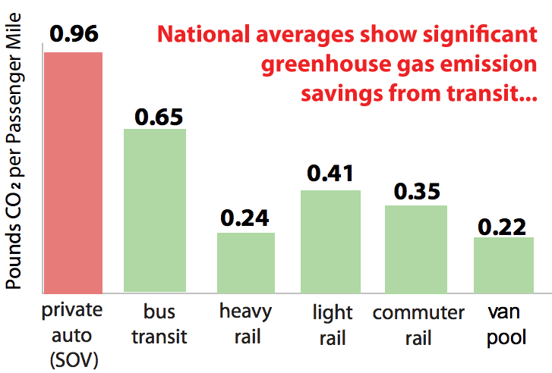

Even so, mass transit vehicles do tend to have lower emissions per passenger mile than privately owned light vehicles. How much so depends on the kind of conveyance.

Photo credit: DOT CO2 (chart by U.S. Department of Transportation)

The challenge

So, as of this moment, it doesn’t appear that public transit is living up to its potential as a force for the environment. But it could.

First, the industry needs to find ways to increase the passenger load per mile to take full advantage of the economies of scale inherent in mass transit. This means agencies must better serve the whole household. Rural transit and paratransit specialize in runs to grocery stores and doctors’ offices, while routed transit’s main stock-in-trade is the commute. Can’t we develop an integrated system that takes the hassle out of both work and home? Is it possible to both serve commuters and still offer them the flexibility to ensure that groceries will get home and the tasks of Mom & Dad’s Taxi Service will be safely fulfilled? And can these objectives be met with the convenience and price point that will make shared rides appealing to the market?

Morris’s piece on Freakonomics cautions that more isn’t always better. Sure, you could send a van around the neighborhood every 15 minutes, but it’ll likely be running with nobody on it but the driver much of the time.

(AASHTO’s findings deserve a little drilldown here. The breakdown of transit trips taken for work and for other uses matches those of household vehicle miles, that is, two-to-one in favor of other uses. “Interestingly, this differs dramatically from some industry-sourced, passenger-survey-based estimates that suggest that commuting constitutes more than half of all travel on public transit,” AASHTO reports.)

Next, capital budgets must keep the fleets up-to-date so that the gains made in passenger-miles aren’t offset by falling behind in fuel efficiency and excessive maintenance – which carries its own carbon footprint.

It all comes down to planning and scheduling: buying just enough rolling stock, performing just enough maintenance, running just enough vehicles along just enough routes making just enough stops. This further implies agencies need to work together – across both geographic borders and modes of transit – to provide the seamless solutions demanded by a public which already has a perfectly good option parked in their driveways. The smarter the transit industry can be, the more mind share and market share it will be able to take away from the family car.

About the Author

William Freedman

I’m the guy who’s traveling across the United States from the Atlantic to the Pacific using only local, publicly available transportation.

%20(200%20x%20100%20px).png)